"Being a journalist is like being on a black list."

|

| Javier Valdez Cárdenas (theguardian.com) |

MEXICO JOURNALISTS

PART 2

Mexico reporter and author Javier Valdez Cárdenas said, “The government's promises of protection are next to worthless if the cartels decide they want you dead.”

And that proved to be the case on a May day in 2017 in Culiacan, Sinaloa, where the fifty-year old journalist was dragged from his car at noon and shot 12 times in front of Riodoce, the newspaper he co-founded in 2003.

As Valdez had presciently stated, “Even though you may have bullet-proofing and bodyguards, the gangs will decide what day they are going to kill you.”

Valdez, well-known for his amiable nature, wide smile and Panama hat, was one of 119 Mexican journalists assassinated since 2000 because they dared to report news about the cartels.

INTERNATIONAL PRESS FREEDOM AWARD

|

| Valdez accepting International Press Freedom Award (cpj.org) |

In a three-decade long career, the award winning reporter chronicled not only stories of Mexico’s organized crime, narco-trafficking, and the corruption of government officials, but also the unseen side—tales from musicians who composed the narco-corridos, mothers whose sons had been murdered, kids from unknown pueblos who dreamed of becoming hitmen. He spoke at a reception in 2011 when he received an International Press Freedom Award by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) where he was introduced as a writer who “combined the grit of a battle hardened reporter with the soul of a 19th century romantic poet.”

In his acceptance speech he said, “The youth will remember this as a time of war. Their DNA is tattooed with bullets and guns and blood, and this is a form of killing tomorrow. We are murderers of our own future."

THIS IS A WAR

“This is a war,” he continued, “one controlled by the narcos, but we the citizens are providing the deaths and the governments of Mexico and the US, the guns.”

|

| Javier Valdez Mural (by Julio Cesar Aguilar, theintercept.com) |

He watched as mayhem ensued, recording in his writings the sins and violence inflicted by cartels on his native citizens. He wrote about countless colleagues’ deaths, but somehow, he carried on. What may have secured the nail in Valdez’s coffin occurred shortly after El Chapo Guzman, notorious Sinaloa Cartel drug lord, was extradited to the US in January 2017, after his third arrest.

Though Valdez’s reporting on the cartels had been tolerated prior to Chapo’s extradition, his attempt to explain the power struggle taking place inside the Sinaloa Cartel after Chapo’s departure may have pushed his once untouchable status to the limit. The splintering, Valdez reported, occurred because there were now two factions in the Sinaloa Cartel. Two of Guzman’s sons, known as the Chapitos, led one faction, while Damaso Lopez, a prison warden and right hand man who helped Chapo in his first prison escape in 2001, led the other. Infighting raged well into February.

DANGEROUS LIASONS

In March a man called the Riodoce offices and spoke to Valdez, requesting a meeting after explaining he had important information. Valdez agreed to meet the man in a car in a parking lot, a risky endeavor. The man was a lieutenant of Damaso Lopez, and while sitting in the car, called his boss then passed the phone to Valdez. Lopez claimed he had not betrayed El Chapo, stating he “loved and admired” his boss. But Lopez also criticized Chapo’s sons, the Chapitos, saying they were “sick with power.”

|

| Remembrance for Javier Valdez (cps.org) |

In his career spanning decades, Valdez had reported from deep within the narco world. Most of his sources were lower down on the food chain, and Valdez protected their identity with anomynity. Printing the words of someone higher up the chain of command, like Damaso Lopez, raised the stakes, pulling Valdez and his paper into the fight. In the end, Valdez decided to print the story, believing the information was important for the public to know.

THE CHAPITOS' END GAME

Before the issue ran, he received a call from a representative of the Chapitos, requesting a meeting at a nearby cantina. The Chapitos’ envoy said that the interview with Lopez could not be published because Lopez was a cartel insurgent. Valdez said it was too late—thousands of copies had already been printed and would go on stands the next day. The next morning when delivery trucks began dropping off papers, cartel affiliates followed, buying up every copy. Few copies were seen by the public.

With that action, Valdez realized he may have reached his expiration date with the Sinaloa Cartel. He contacted the Committee to Protect Journalists and discussed relocating. He ultimately decided against the move however, thinking it would be too difficult for his family, and in the next few weeks, the problem seemed to dissipate.

In an interview with Index on Censorship just a month before his death, he explained some journalists had to flee Mexico under threat of death. In his book, Narco Journalism, he described the Mexico journalist's plight: exiled, murdered, corrupted, terrorized by cartels or betrayed by police or politicos in bed with the cartels.

"Now they kidnap, extort, control the sale of arms, beer, taxis. They control hospitals, police officers, the army, people in government and those who finance them. The omnipresent narco is everywhere.”

Even in the newsroom. In his book Narco Journalism, he wrote that local newspapers hired the occasional reporter on payroll who was a narco plant. “This has made our work much more complicated. Now we have to protect ourselves not only from politicians and narcos, but even other journalists,” he wrote.

Valdez’s final article was about a protest in Culiacán against the deadly attacks teachers face by traveling and working in some of Sinaloa’s most dangerous areas. At least six teachers had been killed in the state that year, 2017.

NO TO SILENCE

In spite of his international profile, Valdez knew he was not protected. After fellow journalist Mirosalva Breach was shot in front of her son in Chihuahua, he tweeted, “Let them kill us all, if that is the death penalty for reporting this hell. No to silence.”

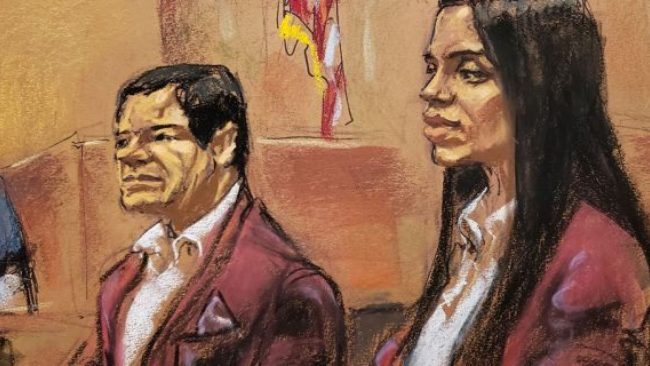

Valdez was silenced forever on May 15, 2017, gunned down in the street as he was leaving to have lunch with his wife. At first the murder was attributed to Damaso Lopez, but Lopez testified under oath during Guzman’s trial in New York City in 2019 that neither he nor his son, Damaso Lopez Serrano, murdered the journalist. He attributed the assassination to the Chapitos, El Chapo’s sons.

But with Mexico's appalling track record on closing out cases, Valdez's true killer may never be known. Suffice it to say it was cartel related.

Valdez’s last book, The Taken—True Stories of the Sinaloa Drug War, tells the stories of ordinary people, caught in a terrifying net—migrant workers, teachers, teens, petty criminals, police officers and local journalists. Building on a rich history of testimonial literature, he recounts stories from people whose world did not center on drugs or illegal activities but on survival and resilience, and how they dealt with fear, uncertainty and the guilt that afflicts survivors and witnesses. His last book was a testament to the people of Mexico.

RIP Javier Valdez.

|

| Javier Valdez (assassination.globalinitiative.net) |

For more information on my writing, check out my website www.jeaninekitchel.com. My first book, a travel memoir, Where the Sky is Born: Living in the Land of the Maya, is available on Amazon as are books one and two in my Mexico cartel trilogy, Wheels Up—A Novel of Drugs, Cartels and Survival, and Tulum Takedown. Subscribe above to keep up to date with future blogs on Mexico and the Maya and the Yucatán.