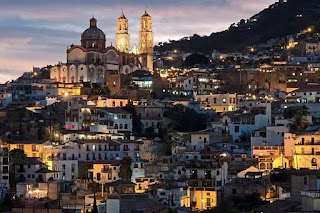

Imagine a city on a hill, the surrounding countryside brimming with the precious metal, silver. That would be Taxco in Guerrero, Mexico, situated between Mexico City and Acapulco. By some estimates, a third or more of all the silver ever mined in the world has come from Mexico's mountains with production still rising. Mexico and silver are synonymous.

Though silver has filled the coffers of great civilizations since 3000 BC— from Anatolia, now modern Turkey, to Greece, the Roman Empire, and Spain, no single event in history rivals the discovery of silver by European conquerers in the Americas following Columbus's landing in the New World in 1492. Those events changed the face of silver and the world forever.

Between 1500 and 1800, Bolivia, Peru, and Mexico accounted for over 85 percent of world silver production and trade as it bolstered Spanish influence worldwide. But long before the Spanish arrived in the Americas, according to author William H. Prescott in his sweeping 1843 epic History of the Conquest of Mexico, the Aztecs used silver to make ceremonial gifts for their gods while also producing ornaments, plates, and jewelry.

|

| Treasures recovered from Spanish galleons |

AZTEC JEWELRY

Along with the precious metals of silver and gold, equally prized by the Aztecs were brightly colored feathers from quetzals and hummingbirds that accentuated the metals. The feathers were difficult to come by and required trade from far away places. Aztec jewelers were incredible craftsmen but unfortunately not much of their work survived the Spanish conquest. Most pieces were melted down but what relics do remain are of excellent quality and design.

Author Prescott paints a picture of the splendors of Montezuma's court where silver and gold ornaments were on full display. And though silver wasn't readily found near the Aztec capitol, it was mined in the northern central highlands towns of Zacatecas and San Luis Potosi. Then around 1558, one of the richest silver veins ever was uncovered in an area near what would become Guanajuato, which led it to become the world's leading silver producer of the day.

In not only Guanajuato but also Zacatecas and San Luis Potosi, grand, faded colonial buildings still stand as the indirect legacies of indigenous slave laborers who worked under horrific conditions to extract vast quantities of silver, along with gold, copper, lead, and iron, for greedy prospectors and wealthy robber barons.

ENTER TAXCO

By the end of the 16th century, Guanajuato had faded and Taxco came to be known far and wide as the silver capital of the world, supplying Europe with the precious metal for many years. But new deposits in Latin America pushed Taxco into obscurity for more than two hundred years until José de la Borda, a Spaniard who immigrated to Mexico, rediscovered silver veins in Taxco in 1716. De la Borda learned the mining trade from his older brother. Taxco was built between 1751 and 1758 by de la Borda who made a great fortune in the silver mines surrounding the town and was considered to be the richest man in Mexico.

WANING INFLUENCE

Taxco de Alcaron, known as Taxco, is Mexico's silver capital and considered a national historic monument, home to 300 silversmiths selling wares throughout the city. Though it's recognized today as an outstanding center for silver production, after de la Borda's death in 1778, Taxco's prominence waned.

Then in the 1930s, Taxco's ancient silver crafts were revived by US resident William Spratling, who hired a master goldsmith to create his first range of items, before engaging a local silversmith, Artemio Navarette—considered the best in Guerrero—to teach him silversmithing. With the combination of Spratling's innovative designs and his mentor's skills, by the early 1940s Taxco became known as a center for silver jewelry, not only in Mexico but also abroad.

SPRATLING'S ARRIVAL

As an architect and artist who had taught in Tulane University's School of Architecture in New Orleans in the mid-1920s, Spratling's appearance in Taxco was an accident waiting to happen. During summers from 1926 through 1928, Spratling lectured on colonial architecture at the National University of Mexico's summer school and had grown familiar with nearby Taxco's winding cobblestoned streets and colonial charm.

|

| Amethyst brooch by Spratling |

In Mexico during the 1920s, worlds collided when painters, writers, and musicians confronted a brave new Mexico after its bloody revolution. Mexico was ready to embrace renewal after the ten-year torment of war that had raged from 1910 to 1920. Artists and artisans across the newly democratized nation were inspired, ready to re-examine their national identity and cultural traditions, having defied the ruling class. It was time to empower the impoverished rural people by embracing their folk traditions and crafts. Both Mexican and American intellectuals began to collect and promote the jewelry and crafts of Mexicana history.

HISTORY AWAITS

|

| Spratling with Diego Rivera, 1940s |

Artists, including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Juan O'Groman, descended upon colonial Taxco. Spratling, a one-time literary hopeful, had already come into contact with others on the writing scene—William Faulkner and Sherwood Anderson—and he soon became friends with Rivera whose friendship broadened his cultural understanding. He began to explore the rugged, unmapped regions of southern Mexico. He moved permanently to Taxco in 1929 and began designing furniture, jewelry, and homewares based on the indigenous motifs he uncovered.

BRINGING IT HOME

As Spratling settled into life in a colonial village, he was inspired by Dwight Morrow, American ambassador to Mexico, who told him that while Taxco's silver mines yielded thousands of pounds of silver over the centuries, little remained in Mexico. That motivated Spratling to establish his first studio in Taxco. The legend of what was to become Mexico's silver capital had begun. Spratling's ability to create stunning pieces of jewelry, flatware, and decorative objects was born.

PRE-COLUMBIAN INFLUENCES

While at Tulane, Spratling had been introduced to pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican art and along with his Mexican travels, these motifs proved a strong influence on his early silver jewelry designs. His studio, named Taller de las Delicias (Workshop of the Delights) grew rapidly and by the late 1930s he employed several hundred artisans to produce his designs. From Mexico, those pieces found their way north of the border through Montgomery Ward catalogs, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Gump's in San Francisco.

|

| Spratling in his Taxco studio |

Known in time as the father of contemporary Mexican silver, Spratling incorporated native materials like amethyst, turquoise, coral, rosewood, and abalone into his creations. Depictions of real and pre-Columbian motifs of discs, balls, and rope designs were typical in his pieces. Art historians say that his use of aesthetic vocabulary based on pre-Columbian art can be compared to the murals of Diego Rivera, in that both artists, along with Frida Kahlo, were involved in the creation of a new cultural identity for Mexico. Spratling's silver designs drew on pre-conquest Mesoamerican motifs with influence from other native and Western cultures.

His work served as an example of Mexican nationalism and gave Mexican artisans the freedom to create designs in non-European forms. For this reason, because of his influence on the silver design industry in Mexico, the monicker, "Father of Mexican Silver," came into being.

A MAN OF THE PEOPLE

Besides pioneering a new concept of Mexican silver design, Spratling developed an apprenticeship system to train new silversmiths. Those with promise worked under the direction of the maestros and in time would go on to open their own shops.

Through Spratling's innovation and artistic expertise, Taxco is the most famous silver town in the world's leading silver-producing country. "Probably eight out of every 10 houses in Taxco has its own silver workshop—there's the kitchen, the bedroom, the bathroom, the living room and the workshop," said Brenda Rojas, director of the William Spratling Museum. "Ninety-five percent of the people in Taxco live from silver. Taxco grew because of silver."

Spratling's work was recognized throughout Mexico for its originality and superior quality. Dr. Taylor Littleton, author of William Spratling: His Life and Art, is the definitive Spratling biography, creating a portrait of the fascinating, intensely driven icon of the mid-20th century, said one reviewer. And from Littleton, "His whole life flowed into everything that he designed."

Reneé d'Harnoncourt, director of New York's Museum of Modern Art and longtime friend, praised 'the climate of understanding' Spratliling built that contributed to the acceptance of Mexican art. "I know of no one person who has so deeply influenced the artistic orientation of a country not his own," she said.

| Silver fertility bracelet by Spratling |

As his business grew, Spratling moved his taller to a large mansion and to manage the costs, incorporated in 1945 to provide cash flow for the company. He sold a majority of the shares to a US investor, Russell Maguire, who ultimately took the company into bankruptcy. William Spratling died in a car accident returning to Taxco from Mexico City in 1966. Spratling was 66.

Parting words soon after his death were solicited from friends and associates. Artist Helen Escobedo said this, "Although he was isolated in Taxco, he was always au jour. The man was an adventurer and nothing was too much for him. He couldn't squeeze enough out of life. He was an extraordinary character. He made his own rules. He was a rough diamond and never attempted to polish it. His charm consisted in being ridiculously generous, extremely interesting...a story teller. His silversmiths respected him. They knew he knew his job. They understood him because he thought in their ways.”

In Taxco, the William Spratling Museum, a three-story building, holds his collection of indigenous artifacts.