|

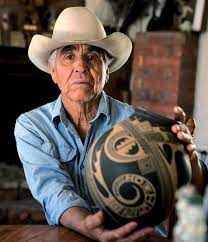

| Juan Quezada Celado in Mata Ortiz |

Juan Quezada Celado died at his ranch in Mata Ortiz, northern Chihuahua, on December 1. The master artisan, famous for resurrecting a pottery style known as Mata Ortiz, was 81.

I became aware of Mata Ortiz pottery and its founder, Juan Quezada Celado, quite by accident after meeting Santa Barbara potter Rebecca Russell at a tai chi class last year. Somehow we started talking about Mexico. She told me her pottery work drew her there and she'd traveled to northern Chihuahua to study with Juan Quezada who'd developed a style known as Mata Ortiz.

I'd lived in Mexico for 17 years and hadn't heard of it. The most common pottery style in Quintana Roo, my stomping grounds, came from Puebla, the Talavera style, characterized by bright colors and diverse patterns with a high glaze finish. Talavera was widely marketed in QRoo, the Yucatan, and throughout Mexico.

Rebecca showed me her business card with a photo of the Mata Ortiz style. It was like nothing I'd seen before, very elegant, different. She spoke with great respect of Quezada and I later researched both the artist and Mata Ortiz pottery.

Juan Quezada's life story reads like a fairytale. It's the story of a poor woodcutter who transformed himself into one of the most famous artists in Mexico. It's also a tale of a dusty Mexican village that learned how to fashion dirt into clay, transforming it into something beautiful.

A young Juan Quezada had been forced to quit school to help his family survive. He picked firewood in the surrounding area where a sophisticated pre-Columbian culture had once thrived around the city of Paquime (also called Casas Grandes). It dominated the region for 300 years around 1200 AD and had been famous for ceramics featuring geometric designs in red, black, yellow, and brown which were traded throughout North America.

The boy found ancient pottery fragments as he worked. He even found shards in his own backyard—both Casas Grandes style and an older style still, Mimes, that dated from 200 AD, characterized by bold black on white zoomorphic designs. With his burro, he eventually went farther into the mountains collecting firewood and picking up bright shards along the way.

Though no one seemed to know about the people who made the pottery, everyone knew of the ruins 15 miles north, Paquimé, the center of the Casas Grandes culture. The mounds on the plains were the remains of the outlying communities that spread for miles around the site. At dusk by the light of his campfire, he'd examine his daily collection of shards, trying to figure out how they had been made. At home he dug clay from the arroyos, soaked it, and tried to make pots. They all cracked. Eventually Juan studied the broken pieces and realized that mixing in a little sand would prevent the cracking. His interest led him to the study of the pre-Hispanic pottery of the ancient cultures so close to his village. In time, he figured out how to make round bottoms similar to the prehistoric pots by making a mold after finding some in the outlying mounds.

Gradually he mastered the process. As a young man, without any instruction, he was making and decorating credible pots for his own pleasure. He had re-created the entire ceramic technology from clay preparation to firing, using only shards to guide him, without help from ceramicists or specialists. But now married, he needed a variety of jobs to keep food on the table for his family—from working as a cowboy to railroad worker, leaving less time to make pottery.

But pottery still enticed him. In 1974 he decided to concentrate on making pots. He could sell enough with local traders to risk leaving his job on the railroad; earnings from the sale of just one pot would outdo what he'd earn on repairing rail tracks. His modest success attracted the interest of his siblings and he began to teach them what he'd learned. He became known as the self-taught interpreter of Casas Grandes pottery, sometimes called New Casas Grandes or Mata Ortiz after the village where it originated.

Initial attempts to sell the pots in his area on a large scale failed, but he had success with border merchants, where his pottery was discovered by an anthropologist, Spencer MacCallum, who tracked Quezada down and helped him break into the larger US market.

What started with the meeting of Quezada and MacCallum led to MacCallum's promotion of the pottery style across the border. He showed Quezada's pieces to museum curators, universities, and gallery owners. MacCallum's salesmanship and perseverance cemented the interest in these important markets which were essential to the potter's survival. An exhibition at the Museum of Man in San Diego, 1997, helped establish Mata Ortiz pottery as a legitimate art movement and helped it to gain momentum. After a slow start in the marketplace, gradual acceptance gave way to a full-flowering of Mata Ortiz styles and skills, a development that even the most ardent admirers had failed to predict.

Today over 350 Mata Ortiz families earn all or part of their income from pottery, thanks to Quezada. The finely painted ceramicware can rival any handmade pottery in the world. Quezada single-handedly resurrected the style and ancient techniques of his ancestors' pottery.

Quezada's work has been displayed in museums in numerous countries and in 1999 he was awarded the prize of Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes in Mexico. Books have been written about him and his style and techniques are well known throughout the world of pottery and beyond. His talent and influence will not be forgotten and his Mata Ortiz pottery style will continue to garner accolades throughout the world. Juan's pottery now sells for thousands of dollars and has found homes with numerous Mexican dignitaries, a Pope, a former US Supreme Court justice, and a former US First Lady. Tourists and art dealers make the trek to Northern Chihuahua in search of his pottery. More important still, Juan Quezada Celado gave his family a skill and art form that ensures a level of economic freedom for not only themselves but for generations to come.

"He taught us all," said Quezada's youngest sister, Lydia, in a 2020 Washington Post article. "He's a talented teacher." RIP Juan Quezada Celado.

If you enjoyed this post, check out Where the Sky is Born: Living in the Land of the Maya, on Amazon. My website is www.jeaninekitchel.com. Books one and two in my Mexico cartel trilogy, Wheels Up—A Novel of Drugs, Cartels and Survival, and Tulum Takedown, are also on Amazon. And my journalistic overview of the Maya 2012 calendar phenomenon, Maya 2012 Revealed: Demystifying the Prophecy, is on Amazon.

Thanks Jeannie.....It was legendary that several other people did figure out the pottery techniques but Juan was the one Spencer focused on.......

ReplyDeleteJuan died in accident doing what he loved doing...looking for new clay bodies and minerals for painting....

I am so glad I learned of him. What a talent and treasure to the art world.

Delete