|

| Mennonites in Campeche at Harvest (Photo Reuters) |

In Cancun we'd often see Mennonites in straw cowboy hats hawking cheese wheels at downtown stoplights. Smack dab in the middle of a thorough-fare, young men in Bib overalls would stand fearlessly on the center line, waving their products as cars zoomed by on both sides. We later learned the Men-nonites had a long history with Mexico and the Yucatán stretching back to the early 20th century.

The Mennonites trace their roots to a group of Christian radicals who emerged during the Reformation in 16th century Germany. They opposed both Roman Catholic doctrine and mainstream Protestant religions and maintain a pacifist lifestyle. They emigrated to North America to preserve their faith.

In the 1920s a group of 6,000 moved to Chihuahua in northern Mexico and established themselves as important crop producers. In the 1980s a few thousand moved to Campeche on the edge of the Maya Forest which is second in size only to the Amazon. According to Global Forest Watch, a non-profit that monitors deforestation, the Maya Forest is shrinking annually by an area the size of Dallas. In Campeche, the Mennonites bought and leased tracts of jungle land for farming, some from local Maya.

|

| Burning Fields in Campeche |

In 1992 Mexico legislation made it easier to develop, rent or sell previously protected forest, increasing deforestation and the number of farms in the state. When Mexico opened up the use of genetically modified soy in the 2000s, Mennonites in Campeche embraced the crop and the use of Round Up, a glysophate weedkiller, designed to work alongside GMO crops, according to Edward Ellis, a researcher at Universidad Veracruzana.

Higher yields meant more income to support large families. For the Mennonites, a family of ten children is not uncommon. They typically live simple lives supported by the land and choose to go without modern-day amenities such as electricity or motor vehicles, as dictated by their faith. But their farm work has evolved to use harvesters, chainsaws, tractors. While most Mennonite communities remain in Chihuahua, now another 15,000 Mennonites also live in Campeche.

|

| Mennonite Girls in Cleared Field (Photo Reuters) |

Presently the tide has turned on deforestation in Mexico and both ecologists and the government that once welcomed the Mennonites' agricultural prowess believe the rapid razing of the jungle by these new ranches is creating an environmental disaster. The Maya Forest is one of the biggest carbon sinks on the planet and the habitat of endangered jaguars, plus 100 species of mammals to which the jungle is home.

A 2017 study published by Universidad Veracruzana showed that properties cleared by Mennonites had rates four times higher for deforestation than other properties. Under international pressure to follow a greener agenda, the Mexican government has persuaded some Mennonite communities to sign an agreement to stop deforesting the land. But not all communities have signed such an agreement.

In speaking to Reuters, a Mennonite school teacher in a pueblo on the edge of the forest stated that the agreement has not impacted the way they farm. The Mennonites have signed on an attorney who states they believe they are being targeted by the government due to their pacifist beliefs while other land destroyers are not bothered.

Between 2001 and 2018, in the three states that comprise forest growth in Mexico, 15,000 square kilometers of tree cover was razed, roughly the size of the country Belize. With changing weather patterns and less rain, harvests are smaller in general for all concerned, both Mennonites and the indigenous Maya.

The Campeche Secretary of Environment, Sandra Loffan, clocked in stating the Mennonites did not always have the correct paperwork to convert forest land to farm land. An agreement was signed last year, 2022, to create a permanent group between the government and Mennonite communities to deal with land ownership and rights, and disagreements that arise including those from locals stating the Mennonites are abusing logging rights.

|

| Typical Mennonite Buggy |

But this is only one of the Mennonites' problems in Mexico. Ten years ago connections between the community and Mexican cartels were exposed when a mule pipeline from Chihuahua to Alberta, Canada, was discovered. In this unlikely alliance, the pacifist Mennonites were growing tons of marijuana for the cartels and shipping it north, smuggling it in gas tanks, inside farm equipment and cheese wheels. For background, in an old ABC interview, Michael LeFay, Immigration and Customs Director in El Paso, stated a Mennonite network emerged long ago. What began with marijuana expanded into cocaine smuggling. When customs officials at the U.S. border looked into a car and saw Mennonites, he explained, officials waved them through. Mennonites were a common sight at the border and frequent travelers from Mexico to Canada because many Canadians from Manitoba and Ontario have Mennonite family members in Mexico.

|

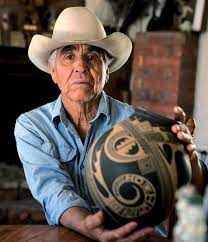

| Mennonite Man with Cheese Wheel |

Though the Drug Enforcement Agency's (DEA) issued a statement decades ago that only a few members of the Mennonite community had links to violent cartels, facts proved them wrong. In the 1990s not all Mennonite families owned land; they fell on hard times. At the same time the tenets of their faith drew questions from a younger generation raised in Mexico where there was no legal age restriction to buy alcohol or cigarettes. Vices began to creep in. It wasn't uncommon, an ABC newscaster reported, to see young Mennonite teens drinking Corona and smoking cigarettes after a Sunday church service once their parents left the church parking lot.

Reports started to trickle in: a Mennonite man was accused of smuggling 16 kilos of coke across the U.S.-Canadian border in 2012. Jacob Dyck faced charges of conspiracy to import $2 million of cocaine and possession for purpose of trafficking.

Then along came the Canadian TV drama Pure, earning a place in Canadian pop culture about Mennonites connected to the cartels. But DEA agents were still trying to get their heads around it, tsk-tsking the outrageous idea that Mennonites had a corrupt streak. DEA Agent Jim Schrant was quoted as saying a "large scale marijuana and cocaine distribution group run by Mennonites with cartel connections seemed bonkers."

Though Schrant was aware that a huge drug distribution group was operating in Mexico and shipping large quantities into the U.S. he believed it was being run by individuals only. Then along came the story of Grassy Lake, Alberta, a rural town of 649 souls where 80 percent of residents were Mennonites. In time the DEA got wise and outed the town as the distribution hub for an international weed and coke smuggling operation linked to the Juarez Cartel.

|

| 31-Hour Drive from Mexico to Canada |

A widely publicized case against Abraham Friesen-Rempel, 2014, had the DEA intercepting 32,500 phone calls believed to be linked to Juarez Cartel drug activity. Although Friesen-Rempel played only a minor role as driver, he'd delivered 1575 pounds of pot for the cartels. Convicted of smuggling drugs, he received a 15-month federal sentence. And so on, and so forth.

It's believed that the cartels lean on the Mennonites because they share a common bond of anti-government sentiment. Staunchly private, the Mennonites shun government interaction and their fierce sense of privacy aligns them with the philosophy of the cartels. Also, for decades they never got a second look at the border. The perfect cover for illicit border crossings.

So now, though the drug implications are tamped way down, the government is extremely dissatisfied with the deforestation done by their farming tech-niques. Mexico's President Andres Manuel Lopez is pressuring them to shift to more sustainable practices. The government plans to phase out glysophate by 2024 which would lower harvest yields and their incomes.

"That's a consequence all farmers, Mennonites and locals, might have to pay to save the environment," said Campeche's Secretary of Environment Sandra Laffon.

If you enjoyed this post, check out Where the Sky is Born: Living in the Land of the Maya, on Amazon. My website is www.jeaninekitchel.com. Books one and two in my Mexico cartel trilogy, Wheels Up—A Novel of Drugs, Cartels and Survival, and Tulum Takedown, are also on Amazon. And my journalistic overview of the Maya 2012 calendar phenomenon, Maya 2012 Revealed: Demystifying the Prophecy, is on Amazon.