|

| Mata Ortiz Pot (by Stanford Magazine) |

Three pots found in a thrift shop just north of the Mexican border in 1976 in Deming, New Mexico, by Spencer MacCallum proved to be the breakout moment for a unique pottery style known as Mata Ortiz.

In the dusty terrain of northern Chihuahua, the discovery of Mogollon pottery shards from a little-known archeological site, Casa Grandes or Paquimé, gave birth to the unique line. (Mogollon is an archaeological culture of Native American peoples from Southern New Mexico, Arizona, Northern Sonora, and Chihuahua). Named after the modern town of Mata Ortiz, the style was generated by Juan Quezada Celado.

PAQUIMÉ

|

| Mogollon-Mimbres Pottery |

A sophisticated, pre-Columbian culture had revolved around Paquimé dominating the region from approximately 1200 to 1500 AD. Its multi-story ruins could rival those of Chaco Canyon National Park in northwestern New Mexico. Paquimé was famous for ceramics that featured geometric designs in red, black, yellow, and brown, which were traded throughout North America.

A young Juan Quezada, who had been forced to quit school after only two years of formal education to help his family survive, picked firewood in the surrounding areas and found ancient pottery fragments as he worked. The boy found shards even in his own back yard—both the Casas Grandes style and an older style still, Mimbres, characterized by bold black on white zoomorphic designs. (The Mimbres culture flourished from 200 to 500 AD). With his burro he eventually went farther into the mountains collecting firewood, picking up bright shards along the way.

|

Paquimé's Massive Roomed Walls (By D. Phillips)

|

Though no one knew about the people who made the pottery, everyone knew of the ruins 15 miles north, Paquimé, the center of the Casas Grandes culture. The mounds on the plains were the remains of the outlying communities that spread for miles around the site. At dusk by the light of his campfire, he'd examine his daily collection of shards, trying to figure out how they had been made. At home he dug clay from the arroyos, soaked it, and tried to make pots. They all cracked. Eventually Juan studied the broken pieces and realized that mixing in a little sand would prevent the cracking. His interest led him to the study of the pre-Hispanic pottery of the Mimbres and Casas Grandes cultures. In time, he figured out how to make round bottoms similar to the prehistoric pots by making a mold after finding some in the outlying mounds.

LEARNING THE ROPES

Gradually he mastered the process. As a young man, without any instruction, he was making and decorating credible pots for his own pleasure. He had re-created the entire ceramic technology from clay preparation to firing, using only shards to guide him. Without help from ceramicists or specialists, he had worked out how the pots were made. But now, as a young married man, he needed to have a variety of jobs to keep food on the table for his family—from working as a cowboy to railroad worker, leaving less time to work with clay.

|

| Mata Ortiz (By TravelThruHistory) |

But pottery still enticed him. In 1974 he decided to concentrate on making pots. He could sell enough with local traders to risk leaving his job on the railroad; earnings from the sale of just one pot would outdo what he'd earn on repairing rail tracks. His modest success attracted the interest of his siblings and he began to teach them what he'd learned. He became known as the self-taught interpreter of Casas Grandes pottery, sometimes called New Casas Grandes or Mata Ortiz after the village where it originated. Now around 350 families from his small village produce this thin-walled, finely painted ceramic ware that can rival any handmade pottery in the world. Quezada had resurrected the style and ancient techniques of his ancestors' pottery.

|

| Quezada's Family Gallery in Mata Ortiz |

In the process, he rescued a village on the cusp of obscurity and put it on a trajectory that has created a thriving pottery district known for production of this original, contemporary folk pottery. Though there was enough evidence from the ancient shards to intuit the spirit of the long lost native aesthetics of a formerly active pottery production center for trade in the 13th and 14th centuries, most of the potters in Mata Ortiz were young and not beholden to historical styles. They created something similar but new—a post modern adaptation of the traditional pottery.

|

| Spencer MacCallum and Juan Quezada, 1976 |

COURTING SUCCESS

Though Juan's initial attempts to sell his pots locally failed, he came to have success with border merchants who sold the pots on the US side where MacCallum discovered them in the thrift shop. An anthropologist and art collector, MacCallum tracked Quezada down and helped him break into the larger US market.

ENTER WALT PARKS

Another stroke of luck for Quezada and Mata Ortiz pottery came through Walt Parks, a financial analyst with a Stanford MBA and a love of pottery, who created an artistic and economic miracle in Mata Ortiz by peddling its pots. He'd met Juan in Palm Springs in 1984 where the potter was teaching a class at an art center. Between that first meeting and 2001, Parks took over 50 trips to Mata Ortiz. In 1993 he authored a book titled The Miracle of Mata Ortiz: Juan Quezada and the Potters of Northern Chihuahua.

Parks called Mata Ortiz before Juan Quezada's pottery renaissance a village with a past but no future. Along with Juan, the former analyst nurtured its growth, bringing the villagers' pots to the US where he arranged exhibitions, classes and acted as an unpaid translator and advisor. When asked why, he responded, "If you'd had a chance to work with Pablo Picasso in a new art movement, wouldn't you have done it too?"

Now, thanks to a couple lucky breaks and the yearnings and talent of a young boy to re-create the beauty he found in ancient pottery shards as he picked firewood in the rugged state of Chihuahua, homeland to the Tarahumara and Apache Indians as well as Spanish, Chinese and Mormon immigrants, Juan Quezada, once a poor woodcutter, has become the Picasso of Mexican ceramics.

PREMIO NACIONAL DE LOS ARTES

Said Spencer MacCallum, Quezada has received the Premio Nacional de los Artes, the highest honor Mexico gives to living artists. "Quezada's life is like a fairy tale. And it doesn't hurt a fairy tale to be true, does it?"

One of Quezada's foremost potters, Jorge Quintana, said, "We owe it to Juan; he's the teacher. Without Juan, Mata Ortiz would have perished like all the other desert towns that relied on the timber industry."

Which is why the people in the area sing corridos—ballads—in honor of Quezada. "All Chihuahua wants to give you thanks," one song says. "To our great teacher, our friend, Juan Quezada."

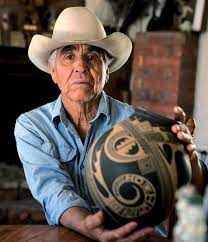

Juan Quezada is 81 years old and father of eight children. He lives a rural life, having moved from the town of Mata Ortiz to a ranch nearby that overlooks the banks of the Palangalas River. He named the ranch Rancho Barro Blanco (White Clay Ranch) in honor of the pottery.

|

| Juan Quezada in Mata Ortiz |

CALIFORNIA CONNECTION

In Santa Barbara, California, 10 West Gallery, an artist-owned cooperative founded by Jan Ziegler, sells Mata Ortiz pottery. The gallery owner makes regular trips south of the border to obtain new inventory and will have new pots this fall. The gallery is located at 10 West Anapamu Street. |

| 10 West Gallery Mata Ortiz Pottery |

|

| 10 West Gallery Mata Ortiz Pottery |